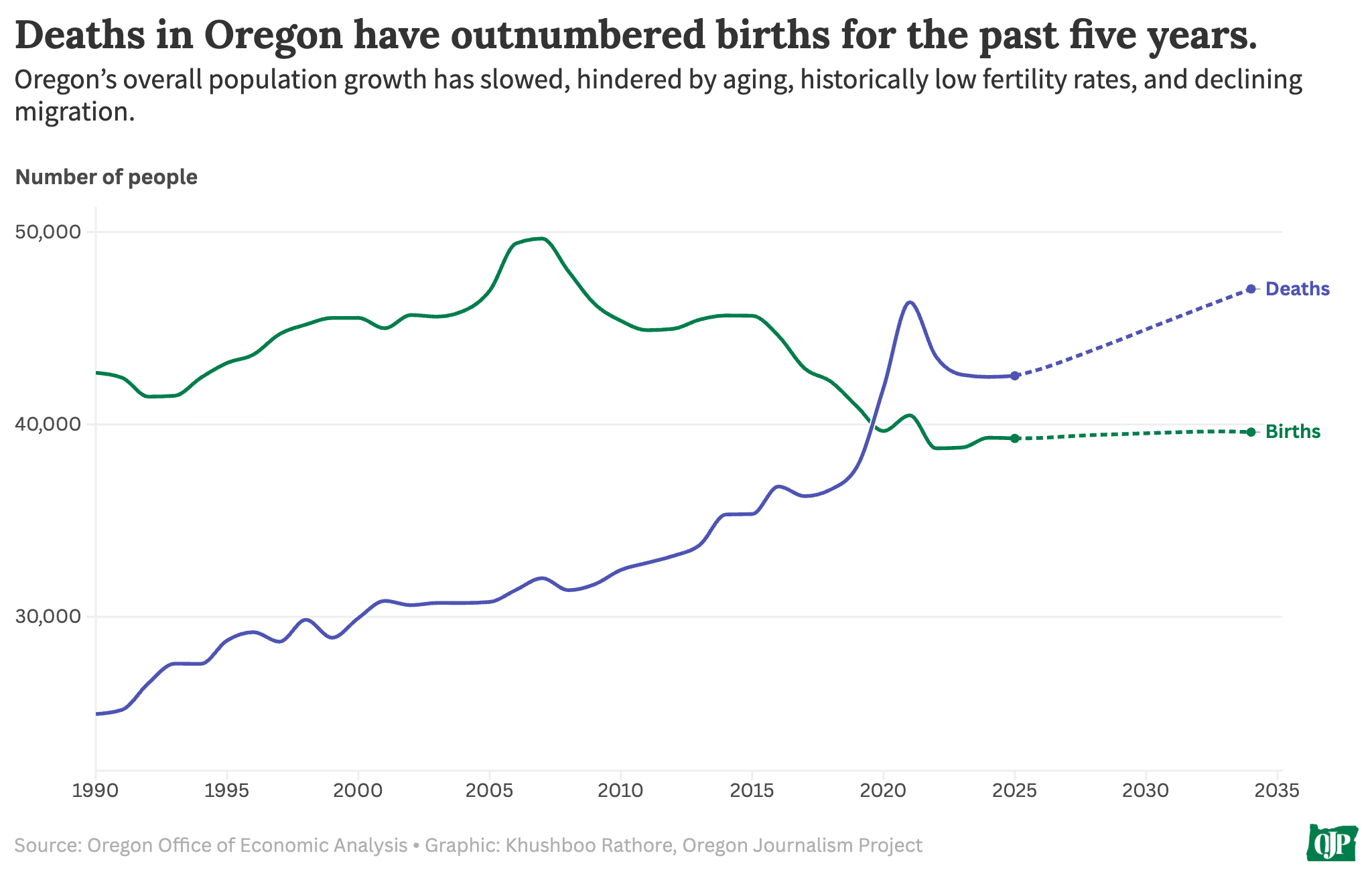

As Oregon’s political and business leaders prepared for a summit later this year, they asked John Tapogna, the former president of the consulting firm ECOnorthwest, to survey the state’s current condition and take a look at its future. What Tapogna found is sobering—more Oregonians are dying than being born, and those being born are entering an educational system whose test scores have plummeted, despite new spending. In short, the boom days are over.

Tapogna identified five major challenges the state faces: a housing shortage; lousy K–12 schools; wildfires; overreliance on income taxes; and ambivalence about growth. He notes that the one that scares him the most—wildfires—is the one over which Oregonians have the least control. Overall, Oregon’s old way of doing things, Tapogna says, won’t work anymore.

“Many of Oregon’s systems—our schools, regulations, land use rules and permitting processes—were built for a different time, to solve yesterday’s problems,” he says. “But the future has never looked less like the past than it does right now.” His findings ought to be a wake-up call for the state’s policymakers and business leaders. Will they listen?

The Oregon Journalism Project sat down with Tapogna for an interview that has been edited for brevity and clarity.

OJP: Which of your findings was most surprising to you?

John Tapogna: For me, the overarching story here is that the Tom McCall era is over. We are used to population flowing into Oregon in large numbers. That’s finished, in part because of slowing in-migration and because Oregonians are dying faster than they are being born.

What else surprised you?

Just how rapidly our school performance has collapsed. In the early 2000s, Oregon was dead in the middle in terms of National Assessment of Educational Progress performance. And a decade of pretty strong, sustained investment brought spending back up close to the U.S. average in budget terms. But now we are one of the lowest-performing, if not the lowest-performing, states, taking demographics into account.

So, as we increased funding, performance got worse? Why?

It coincides with the relaxation of federal accountability around 2015 or ’16. There was an era of No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top—federal policies that forced accountability into the states. In Oregon, test scores started to fall before the pandemic, and then they kept going. Some states developed a homegrown accountability system, and a culture around at least respecting standardized tests, understanding they’re giving you some information that’s useful. Oregon doesn’t have that. [Editor’s note: In 2015, then-Oregon Gov. Kate Brown signed House Bill 2655, which required school districts to send notices allowing parents to opt out of achievement exams for their children. Oregon has not hit the federally mandated 95% opt-in testing rate since.]

Some people say Oregon’s poor test results are a function of property tax limitations that started around 1990.

Well, somehow we were producing close to average results for a long time after those ballot measures. If Oregon was out to prove that money doesn’t make a difference in educational results, they did about as good a job as anybody could.

You’ve also identified high housing prices and homelessness as major risks. How did we get here?

Housing production collapsed after the Great Recession. We do also have a sort of a cultural ambivalence about growth in this state that has a whole series of policies aligned with it. We built a bunch of regulatory policies in the 1970s and the ’80s, and maybe kept building them in the ’90s, to slow and tame the growth that was coming. That machinery was very well designed for its times, but if left completely unchanged, I think it could do serious harm to the future of the Oregon economy. That is, if we don’t step back and say 2025 is different from 1975.

When she took office, Gov. Tina Kotek announced a goal of building 36,000 new housing units a year. We haven’t come close to that goal. Why not?

Some of it is the macro economy. Interest rates are higher, construction costs are high. As House speaker, Gov. Kotek started working on housing in 2015 and has pushed through nation-leading public policy through legislative processes that are only now in rulemaking. So a lot of good work has been done.

>>READ MORE: Oregon’s Choice: Grow modestly or not at all

It feels a little bit like your conclusion on education—that we’ve put a lot more money in, but our results are worse.

What’s different is, you see that same downturn in housing production in recent years in other places, such as Washington, but you don’t see the same downturn in education.

Yet over the past four decades, housing prices here have gone up more than in all but a handful of states.

As a state, we’ve made certain decisions. For example, we’re one of the least urbanized of all the states. That goes back to Senate Bill 100 [Oregon’s land use planning bill]. It’s worth thinking about how does it need to change, or how does it need to be updated to anticipate what appears to be a 25-year period of slow growth.

So you think SB 100 might be part of the reason housing is unaffordable or unavailable to many people?

It’s not only the land use regulations; it’s our permitting processes, it’s the degree of neighborhood control and local control over how much housing there is. Have we been driving along with the emergency brake on, with a system of machinery, not just Senate Bill 100, but the entire sort of environment of approvals and processes and timelines, etc., that aim to slow and tame growth? That’s part of what’s made many people want to live here. It’d be an endless strip mall to Salem, but that machinery, unadjusted, could do some serious harm to the economy.

What about Oregonians’ views on growth?

In other parts of the country, there is an enthusiasm about job creation and enthusiasm about the future and innovation. Here, it’s more of a culture of conservation.

You’ve identified overregulation as a problem. Is that opinion or objective fact?

Researchers from George Mason University came up with a quantitative count in various regulatory categories. They’ve got Oregon at No. 7 in the country. Now, this isn’t a prescription to do an Elon Musk DOGE move on the regulatory structure, but it’s easy to find examples of excessive regulation. But British Columbia went through a process where they said, for every new regulation, managers have to go find two to take out until we start bringing the number down. It turned agencies into regulatory managers, instead of simply regulation writers.

You’ve identified the state’s overreliance on income tax as a risk. So how should we change our system of taxation?

The technical answer to that is easy: pass a sales tax, reduce the income tax, and maybe increase the property tax a little bit. As a state, we’re fourth highest in terms of the share of personal income devoted to income taxes.

Oregon’s mental health and K–12 educational systems are both decentralized relative to some more successful states. Should Oregon rethink its love of local control?

That’s a worthy area of investigation. Having 197 school districts each negotiate salaries with unions, when their budgets are being set in one place [the Legislature], is questionable. With housing policy, you’re seeing a move to pull away some of the power from the neighborhoods and have the state have a little bit more authority about what’s getting built where, and not allowing individual neighborhoods to make that choice.

Why is Oregon so interested in having these decentralized functions that are such an important part of people’s lives?

There is a social libertarian strain here. We’re not economically libertarian, because we like regulation. But Oregonians leaned into drug decriminalization, into death with dignity, etc. There’s something about we’re out here in the West—the individual knows best. We don’t look to an authority or to higher levels of government for answers or accountability.

Do you think that’s a problem?

I see problems, most obviously in the education sector. I think some more coherent oversight from the state and reporting and accountability would be a good thing.

What is the takeaway from the review you’ve just completed?

We’re in completely unfamiliar territory. Our entire history has been that we were on the edge of nowhere, then railroads and highways and fibers connected us. And then, when people found Oregon, they came rushing in. It kept going up until seven or eight years ago. But if you look forward, the future looks less like the past than it has ever looked in our lifetime.

If you had to pick one of the challenges Oregon faces, which one scares you the most?

Wildfires. It’s the toughest one to think about. If you could take one risk off the board, that would be it, in part because it threatens Oregon’s greatest comparative advantage.

This state has been run by one political party for the past four decades. In so far as politics makes a difference in the livelihoods of people who live in that state, is that an issue?

If I think through my five challenges, you know, Tom McCall was a Republican. He created Senate Bill 100. That’s not a partisan issue. I think the ambivalence about growth is a highly bipartisan issue and drives a fair bit of this with respect to testing and the lack of accountability culture inside of the schools.

Maybe Oregon is exactly where we want to be—a no-growth state. Who cares if our kids are educated, and who cares if life is too expensive? Maybe the system is working just the way it’s supposed to.

Well, it’s working the way it was supposed to work for 35 years, and it was designed to do what it did, and it did it well. But now we don’t have the same problems as we had in the ’70s or the ’90s. We’re in a different space. For a long time, we were leveraging our second paycheck [Oregon’s natural beauty] to draw people here, but because of the high housing prices, because of the conditions of the schools, that talent’s not going to flow in as it used to.

This story was produced by the Oregon Journalism Project, a nonprofit investigative newsroom for the state of Oregon. Learn more at oregonjournalismproject.org.

Story published under a Creative Commons Attribution – No Derivatives 4.0 License.